A while ago, React introduced React Hooks. Since version 0.59, you can also use them in React Native.

What are React Hooks?

React Hooks are a way to use stateful functions inside a functional component. Functional components are components written as a function, so they take some input (props) and return a React Element. Before React Hooks, you would need to write a JSX (JavaScript and XML) class that extends from the React Component, in order to access state or lifecycle related code.

So in short: with React Hooks you can write leaner code, reuse code (functions) and make everything more maintainable and testable. In the end, the more time you spend on making your code maintainable, the less time someone else will lose by trying to understand your code.

Also, if you reuse code rather than have duplicates, you save time on refactoring and have potentially less sources of bugs (fix something in one place means you also have to fix it at all other places).

A breakout on the Lifecycle of a React Component

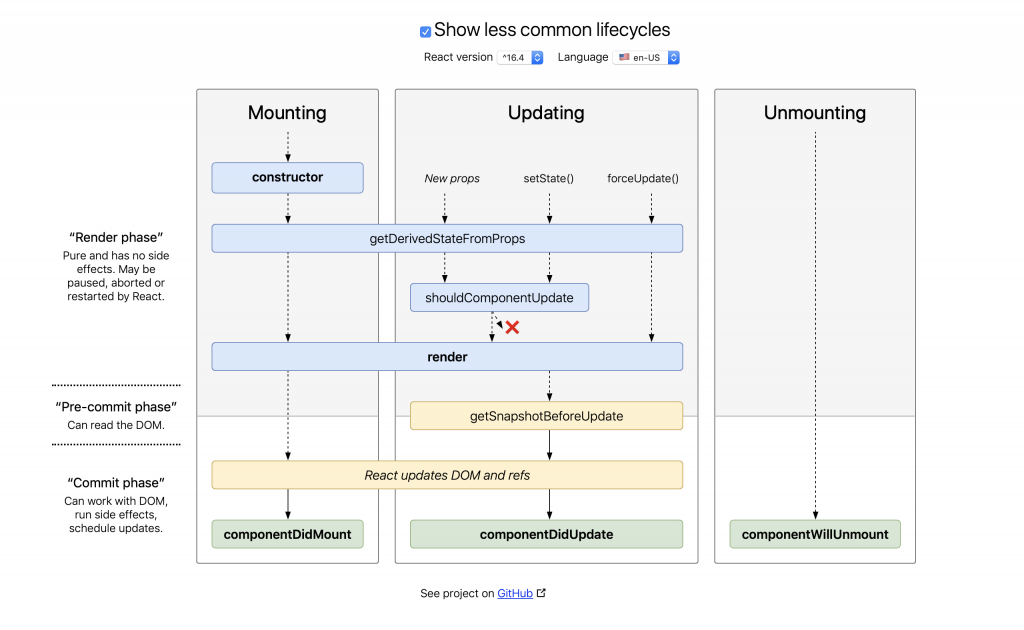

I don't want to go deep on the lifecycle, since React already has a great documentation on that. There are some important things that you should know: rendering, component mounting, the constructor as well as props and state. For a good lifecycle overview you can have a look at the following:

These are the most important things you should know about a React Component and its lifecycle:

Props

Props are input of a component, so it is something you put into a component when you create it. Per definition props cannot change, but you can add a function to the props that do that for you (could be confusing).

State

State is something that can dynamically change (like a text input) and is always bound to something (a component for example). You can change the state by using the setState() function, which only notifies the component about a state change. Take a look at the following example and common pitfall with React and setState:

| // not so good | |

| console.log(this.state.test); // 5 | |

| this.setState({ test: 12 }); | |

| console.log(this.state.test); // might be 5 or 12 | |

| // good | |

| this.setState({ test: 42 }, () => { console.log(this.state.test); // 42 }); |

Constructor

The constructor is not always necessary to have. However, there are some uses cases: initializing state and binding methods to this. What you definitely should not do there is invoking long-running methods, since this may slow down your initial rendering (see the diagram above). So a common component and constructor could look like the following:

| class MyComponents extends React.Component { | |

| constructor(props) { | |

| super(props); | |

| this.state = { | |

| test: 42 | |

| }; | |

| this.renderSomeText = this.renderSomeText.bind(this); | |

| } | |

| // you could also do this, so no constructor needed | |

| state = { | |

| test: 42, | |

| } | |

| renderSomeText() { | |

| return <text>this.state.test</text> | |

| } | |

| } |

If you don't bind method in the constructor and only initialize the state, you don't even need a constructor (save code). See my article about React Performance here, if you don't know why you should bind certain methods. This also has some valueable code examples.

Component did mount and will unmount

The componentDidMount lifecycle method is invoked only once after the component was rendered for the first time. This could be the place where you do requests or register event listeners, for example.

Apart from that, the componentWillUnmount lifecycle method is invoked before the component is getting "destroyed". This should be the place where you cancel eventually running requests (so they don't try to change the state of an unmounted component or something), as well as unregister any event listener you use. Lastly will prevent you from having memory leaks in your app (memory that is not being used is not released).

A problem probably many (and also I) ran into was exactly what I described in the last paragraph. If you use the Window setTimeout function to execute some code in a delayed manner, you should take care of using clearTimeout to cancel this timer if the component unmounts.

Other lifecycle methods

The componentWillReceiveProps(nextProps) or from React Version 16.3 getDerivedStateFromProps(props, state) lifecycle method is being used to change the state of a component when its props changed. Since this is a more complex topic and you probably use (and should use) it rarely, you can read about it here.

Difference between Component and PureComponent: You might have heard about React's PureComponent already. To understand its difference, you need to know that shouldComponentUpdate(nextProps, nextState) is used/called to determine wether the change in props and state should trigger a re-rendering of the component. The normal React.Component always re-renders, on any change (so it always returns true). The React.PureComponent does a shallow comparison on props and state, so it only re-renders if any of them have changed. Keep in mind that if you change deeply nested objects (you mutate them), shallow compare might not detect it.

Where do Hooks fit into the Component Lifecycle?

If you ask yourself where hooks fit into this lifecycle, the answer is pretty easy. One of the most important hooks is useEffect. You pass a function to useEffect, which will run after the render call. So in essence, it is equal to componentDidUpdate. If you return a function from the useEffect's passed function, you can handle the componentWillUnmount code. Since useEffect runs after every render (which might not always make sense), you can limit it to being closer to componentDidMount and componentWillUnmount by passing [] as a second argument. This tells React that this useEffect should only be called when a certain state has changed (in this case [], which means only once).

The most interesting hook is useState. It's usage is pretty simple: You pass an initial state and get a pair of values (array) in return, where the first element is the current state and the second a function that updates it (like setState()). If you want to read more about hooks, check out the React documentation.

Lastly, I want to present a simple example of a React Native component with React Hooks. It contains a View with a Text and Button component. By clicking the button, you increase the counter by 1. If the counter reaches value 42 or greater, it stays at 42. You can argue if it makes sense or not. Especially since the value will shortly be increased to 43, then render once, then the useEffect will set it back to 42.

| import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react'; | |

| import { View, Text, Button } from 'react-native'; | |

| export const Example = () => { | |

| const [foo, setFoo] = useState(30); | |

| useEffect(() => { | |

| if (foo >= 42) { | |

| setFoo(42); | |

| } | |

| }, [foo]) | |

| return ( | |

| <view> | |

| <text>Foo is {foo}.</text> | |

| <button onpress={() => setFoo(foo + 1)} title='Increase Foo!' /> | |

| </view> | |

| ) | |

| } |

Conclusion

React Hooks are a great way to write even cleaner React components. Its natural ability to create reusable code (you can combine your hooks) makes it even greater. The fact that cleaning side effects (subscriptions, requests) happen for every render by default helps avoid bugs (you may forget unsubscribe), as stated here.